The Restoration of Vision: Havdalah, Fertility, and Intentionality

I. Exertion, Depletion, and Restoration

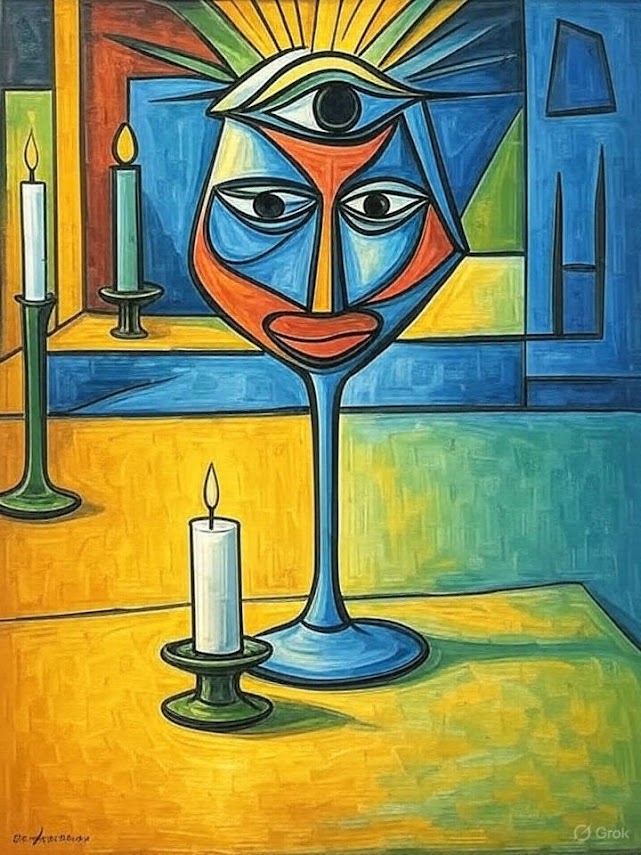

The Talmud (Shevuot 18b) states that one who recites Havdalah over wine merits to have male children. While the connection between ritual separation and fertility seems opaque, it can be explained through Chazal’s physiological framework. The Gemara in Niddah (31a) records Rava’s advice: “Ha-rotzeh she-yihyu kol banav z’kharim, yiv’ol veyishneh” — one who wants all his children to be male should engage in repeated intercourse. This form of physical exertion is demanding, and as Maimonides notes, frequent sexual activity weakens the body and reduces eyesight. The Talmud (Berakhot 43b) draws a similar connection between exertion and vision loss: taking large strides diminishes eyesight by 1/500, a symbolic measure of depletion. That vision, the Talmud says, is restored throug Kiddush at the start of Shabbat.

Tosafot (Pesachim 100b), citing Rav Netronai Gaon, explains this as placing some of Kiddush wine in the eyes. Although the Talmud does not mention Havdalah, later halakhic practice understands both entry and exit from Shabbat — sanctification and separation — as spiritually parallel moments. Perisha (Orach Chaim 269:2) explains the custom to place Havdalah wine on the eyes, not Kiddush wine, due to Shabbat restrictions on healing; thus, the restorative act is delayed until Shabbat’s close. The structure that emerges is clear: to bear male children, one must engage in repeated intercourse, which causes physical depletion, particularly of vision. Havdalah wine — like Kiddush wine — restores what was lost. One who consistently recites Havdalah over wine is thus able to sustain the cycle of exertion and restoration necessary to conceive sons.

II. Symbolic Reading: Intention, Clarity, and Separation

Beyond physiology, this teaching reflects a symbolic truth. Physical exertion and sensual indulgence cloud not just the body but the mind — they pull one into reactivity, instinct, and diminished clarity. The eye, in this framework, represents insight and judgment. Desire, fatigue, and stress can narrow one’s vision, figuratively as well as literally. Shabbat disrupts this cycle: a sacred pause in the noise of the week that offers rest, reintegration, and spiritual realignment.

Havdalah, marking the boundary between sacred and profane, becomes the ritual hinge on which this realignment turns. The act of separation is not merely withdrawal but an act of focus — of reclaiming intention. In rabbinic and symbolic thought, zachar represents agency, initiative, and intentionality — as opposed to passive receptivity or emotional reactivity. The Talmud’s instruction to “engage and repeat” (yiv’ol veyishneh) is not just about frequency but about willful, sustained direction.

Thus, Havdalah wine — which restores vision — becomes a metaphor for the restoration of intentional living. To bring forth zacharim, understood as clarity, legacy, and purpose, one must live not by reaction but by deliberate separation and sanctification. The weekly return to selfhood, through Havdalah, makes such generative focus possible.

Comments

Post a Comment