Disovering Antoninus: Identifying the Talmudic Emperor as Septimius Severus - A Counter Narrative of Historical Memory

Abstract:

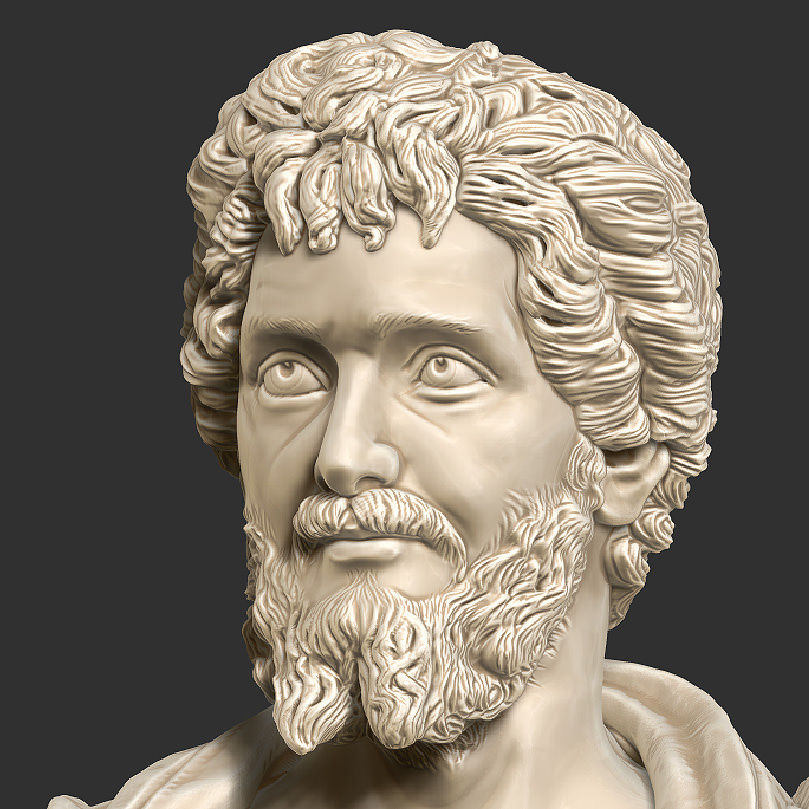

The enduring enigma of "Antoninus" in the Babylonian Talmud, the close Roman imperial confidante of Rabbi Judah the Prince, has long defied singular historical identification, leading scholars to posit a composite figure drawing from various emperors of the Antonine dynasty. This article challenges that prevailing view, proposing that Septimius Severus (reigned 193–211 CE) served as the singular historical referent for the Talmudic Antoninus, unifying previously disparate narrative threads into a coherent and historically grounded account. Through a critical re-examination of key Talmudic narratives—including the alleged requests for senatorial approval, the cryptic "Gira" story (with its nuanced, bidirectional plant counsel), the strategic "vegetable plucking" metaphor, the discussions on secrecy (underpinned by a pervasive atmosphere of paranoia and the life-threatening risks involved in clandestine consultations), and the significant phrases "Antoninus bar Asveirus" and "Asveirus bar Antoninus"—all found primarily in Avodah Zarah 10a-10b, and the fraught relationship between his sons, Caracalla and Geta, particularly the politically charged atmosphere surrounding Geta's perceived allegiances with the Senate, this analysis reveals a sophisticated layer of communication that often necessitated coded exchanges due to inherent risks. Crucially, this re-identification positions the Talmud not as an ahistorical document, but as a preserver of alternative historical memory, offering insights into imperial personalities and events that challenge the biased distortions found in contemporary Roman sources. This provides a more consistent and plausible historical interpretation of these pivotal rabbinic-imperial encounters, shedding new light on Jewish-Roman relations and the complex nature of ancient historical records.

Keywords: Antoninus, Septimius Severus, Rabbi Judah the Prince, Talmud (Avodah Zarah 10a-10b), Roman Empire, Jewish-Roman relations, Imperial succession, Geta, Plautianus, Rabbinic literature, Coded communication, Historical memory, Bias, Dio Cassius, Antoninus ben Asveirus.

I. The Talmudic Narratives: An Overview (Avodah Zarah 10a-10b)

The Babylonian Talmud, particularly in Tractate Avodah Zarah 10a-10b, presents a series of compelling and often enigmatic narratives detailing the profound friendship and intellectual exchanges between Rabbi Judah the Prince (Rebbe), the spiritual and political head of the Jewish community in Roman Palestine, and the Roman Emperor "Antoninus." These accounts consistently portray an unusual level of intimacy and mutual respect, with the Emperor frequently seeking Rabbi Judah's counsel on matters ranging from philosophy and theology to pressing imperial affairs. The text presents these interactions in a specific sequence, which is crucial for understanding their coded messages:

Dynastic Succession and Tiberias's Status: The narrative opens with a discussion about how a king's son might become king "by request." Antoninus then explicitly states his two desires from the Roman Senate: "I desire that Asveirus my son rule after me, and that Tiberias be made a kalanya (colony), and if I tell them one, they will not do it; two, they will not do it." Rabbi Judah responds with a cryptic riddle: "He [Rabbi] brought a man, seated him on another, and gave the upper one a dove (in his hand), and said to the lower one: Tell the upper one to make the dove fly from his hand." Antoninus correctly deciphers this, stating, "Learn from this that he is telling me this: You ask them [the Senate] that 'Asveirus my son rule after me,' and tell Asveirus that he [the son] should make Tiberias a kalanya." This exchange directly reveals the Emperor's priorities and Rabbi's strategic counsel.

Strategic Elimination of Enemies (The "Vegetable Plucking" Metaphor): Immediately following, Antoninus complains to Rabbi Judah: "The Roman notables distress me." Rabbi Judah responds by taking Antoninus into a garden and "every day he [Rabbi] would uproot a radish from the row before him [Antoninus]." Antoninus correctly interprets this as: "You kill them one by one, and do not contend with all of them [at once]."

The Necessity of Secrecy: A significant interlude then occurs, where the text directly addresses the clandestine nature of their meetings. The question is posed: "And why not tell him explicitly?" Antoninus responds: "The Roman notables will hear of me and distress me." The question continues: "And why not tell him in a whisper?" The answer is given with a quote from Ecclesiastes (10:20): "Because it is written: 'For a bird of the heavens will carry the voice.'" This highlights the extreme caution required for their consultations.

The "Gira" Story (Daughter's Illicit Relations): Following the discussion on secrecy, Antoninus has "a daughter whose name was 'Gira,' she was doing isura (illicit relations)." Rabbi Judah responds with a series of plant names exchanged between them: "He [Antoninus] sent him [Rabbi] 'gargira' (rocket/arugula); he [Rabbi] sent him [Rabbi] 'kusbarta' (coriander); he [Antoninus] sent him [Rabbi] 'karate' (leeks); he [Rabbi] sent him [Rabbi] 'chasa' (lettuce/mercy)." This appears to be a coded exchange concerning the "daughter's" illicit behavior.

Antoninus's Generosity and Concern for Legacy: A shorter anecdote describes Antoninus regularly sending Rabbi Judah "crushed gold in baskets, and wheat on their mouths." When Rabbi Judah states he doesn't need it, Antoninus replies: "Let it be for those who come after you, so that they [the future emperors] will give to those who come after you, and those who come from among them [future emperors] should come out against them [future sages]." This emphasizes a concern for the enduring relationship between the imperial house and the Nasi.

Extreme Measures for Secrecy (The Tunnel): The text concludes the main series of anecdotes by reiterating the extent of their clandestine relationship: "He [Antoninus] had a certain tunnel that led from his house to Rabbi's house. Every day he would bring two slaves, one he would kill at the entrance to Rabbi's house, and one he would kill at the entrance to his own house." This vivid detail underscores the life-threatening risks associated with their secret meetings.

These stories, while rich in detail, have historically presented chronological and interpretive challenges, leading to varied scholarly attempts to identify the elusive "Antoninus."

II. The Roman Empire from the Antonines to the Severans: Dynastic Shifts and the Quest for Legitimacy

To understand the riddle of the Talmudic Antoninus, it is essential to trace the dynastic landscape of the Roman Empire leading up to the period of Rabbi Judah the Prince.

The Nerva-Antonine Dynasty (96-192 CE) followed the Flavian emperors and is often heralded as a golden age of Roman imperial rule. It began with Nerva (96-98 CE), who established the practice of adoptive succession, choosing capable individuals as his heirs rather than relying solely on biological lineage. This era continued with:

- Trajan (98-117 CE), a highly successful military emperor who expanded the empire to its greatest territorial extent.

- Hadrian (117-138 CE), known for consolidating the empire's borders and his extensive building projects.

- Antoninus Pius (138-161 CE), whose reign was marked by peace, stability, and good administration. It is from him that the name "Antoninus" gained its significant positive connotation, becoming a byword for a just and legitimate ruler.

- Marcus Aurelius (161-180 CE), co-reigned with Lucius Verus (161-169 CE), a Stoic philosopher-emperor who, despite his philosophical inclinations, spent much of his reign defending the empire from barbarian incursions.

These five emperors (Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius) are famously referred to as the "Five Good Emperors" by later historians, particularly Niccolò Machiavelli, due to the perceived stability and prosperity of their reigns.

The "good" Antonine period, however, came to an end with Commodus (180-192 CE), Marcus Aurelius's biological son. Commodus abandoned his father's policies, alienated the Senate, and descended into tyranny, eventually being assassinated in 192 CE. His murder plunged the Roman Empire into immediate turmoil, shattering the illusion of stable imperial succession and ushering in a period of civil war.

The year 193 CE is known as the "Year of the Five Emperors": a chaotic and brutal power vacuum following Commodus's death. Several claimants emerged, including Pertinax, Didius Julianus, Pescennius Niger, Clodius Albinus, and Septimius Severus. This period saw rapid assassinations and military confrontations across the empire as various factions vied for supreme power.

Ultimately, Septimius Severus emerged victorious from this civil war, establishing the Severan Dynasty (193-235 CE). Severus then focused on establishing a stable dynasty, with his sons Caracalla (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus, who at 7 years old was renamed Marcus Aurelius Antoninus in 195 CE) and Geta (born Publius Septimius Geta) as his intended successors. Aware of the need for legitimacy after a period of such instability, and to link his nascent dynasty to the respected tradition of the "good emperors," Severus undertook a politically astute maneuver. In 195 CE, he posthumously declared himself the adopted son of Marcus Aurelius. This strategic adoption was crucial: it allowed Severus and his sons to legally bear the highly respected and popular name "Antoninus."

Despite this clear historical development, scholars have long debated the precise identity of the Talmudic Antoninus. As discussed in the previous section, the traditional Antonine emperors (Pius, Marcus Aurelius) and even Caracalla have been proposed, but each struggles to fully align with all the nuanced details of the rabbinic narratives. This article will argue that acknowledging Septimius Severus's strategic adoption of the Antonine name is the key to unlocking the puzzle, as he uniquely fits the entire range of complex interactions depicted in the Talmud.

III. Introduction

The Babylonian Talmud, particularly in Avodah Zarah 10a-10b, depicts a unique and profound relationship between Rabbi Judah the Prince (d. c. 220 CE), head of the Jewish community in Roman Palestine, and a Roman emperor known simply as "Antoninus." These dialogues, encompassing philosophy, theology, and pressing imperial affairs, have long puzzled scholars due to the difficulty in identifying a single historical figure who fully aligns with the nuanced details. The prevailing "composite theory" posits Antoninus as an amalgam of various emperors from the Antonine dynasty, a solution that, as this article contends, fails to account for the coherence and specificity evident in the rabbinic narratives.

This article challenges the composite theory, proposing instead a singular identification: Septimius Severus (reigned 193–211 CE). A meticulous re-examination of these Talmudic texts, informed by a deeper understanding of Severan imperial policy, family dynamics, and the political climate of the Eastern provinces, reveals how Severus’s deliberate adoption of the Antonine legacy, his prolonged presence in the East, his dynastic ambitions, and the dramatic interplay between his sons and the powerful Praetorian Prefect Plautianus, offer a far more consistent and plausible framework for interpreting these narratives. Crucially, by grounding these narratives in the context of Septimius Severus—and re-interpreting key phrases like "Antoninus ben Asveirus" (אנטונינוס בן אסוירוס) as a precise identifier for Severus himself—this study argues for the Talmud's role as a preserver of distinct historical memory, offering a valuable counter-narrative to the often-biased Roman histories. This analysis will demonstrate how the Talmud provides a unique glimpse into imperial personalities and events from an Eastern perspective, reflecting the extreme dangers inherent in such high-level political consultations.

IV. Re-Examining the Talmudic Narratives: Septimius Severus Unveiled

A. The Philosophical and Personal Relationship:

The Talmud frequently portrays Antoninus and Rabbi Judah engaging in profound philosophical discussions, often in secret, emphasizing mutual respect and intellectual curiosity. This fits well with the character of Septimius Severus. Though often depicted in Roman sources like Dio Cassius as a stern military man, Severus's North African background and, particularly, the intellectual circle fostered by his highly educated Syrian wife, Julia Domna, reveal an openness to diverse philosophical and religious traditions. Domna was known to patronize sophists and philosophers, making it entirely plausible that the imperial court, while in the East, would have sought out the wisdom of a renowned sage like Rabbi Judah. This engagement reflects a broader curiosity within the Severan court to explore intellectual frameworks beyond traditional Roman stoic philosophy. The emphasis on secrecy, as depicted in the stories (e.g., Antoninus visiting via underground tunnels, discussed further below), further aligns with the political sensitivities of an emperor consulting a non-Roman religious leader on matters that might be perceived as unconventional by the Roman elite.

B. Unpacking the Naming Conventions: "Antoninus bar Asveirus" and "Asveirus bar Antoninus"

The identification of the Talmudic Antoninus as Septimius Severus is crucially illuminated by the nuanced and seemingly contradictory naming conventions involving "Asveirus" found in the Talmud.

The most direct and explicit identifier for the emperor in dialogue with Rabbi Judah is "Antoninus bar Asveirus" (אנטונינוס בר אסוירוס), which appears notably in Avodah Zarah 10b (in the context of his query about the World to Come/afterlife) and in Tractate Sanhedrin 91a-b. In our framework, this phrase, literally "Antoninus, son of Asveirus," functions as a dynastic or familial identifier for Septimius Severus himself. It signifies "Antoninus, who is of the house/line of Severus," or more simply, "Antoninus the Severan." This interpretation acknowledges a common linguistic transformation in Talmudic Hebrew and Aramaic, where foreign names often acquire a prosthetic 'Aleph' (א) at the beginning (e.g., Vespasian appearing as Aspasianus [אספסיינוס]). This elegantly ties the name "Antoninus" to Septimius Severus, acknowledging his adopted imperial name while simultaneously clarifying which Antonine-claiming emperor is being discussed in a rabbinic context sensitive to lineage.

Now, let's address another critical phrase: at the opening of Avodah Zarah 10a, Rabbi Judah is quoted as saying, "אַסְוִירוּס בַּר אַנְטוֹנִינוּס דִּמְלַךְ" (Asveirus son of Antoninus who reigned). This specific phrasing has long presented a significant challenge for traditional scholarship; it cannot be easily reconciled with common identifications for "Antoninus" (such as Antoninus Pius, who had no biological son named Severus), making it problematic within those frameworks.

However, within this article's framework, where the primary "Antoninus" is identified as Septimius Severus, the phrase "Asveirus bar Antoninus" takes on a clear and coherent meaning. Here, 'Asveirus' refers to the Severan dynastic name, and the phrase as a whole refers to Septimius/Antoninus's biological son who inherited both the Severan name and the Antonine imperial title. This explicitly points to Caracalla, who was the son of Septimius Severus and who also adopted the name Antoninus. This interpretation ("Severus, son of Antoninus") perfectly aligns with historical reality, as Caracalla (who was part of the Severan dynasty and also an 'Antoninus') indeed "reigned" (דִּמְלַךְ) after his father. This highlights the complex intertwining of their names within the Severan dynasty and makes the subsequent narrative on 10a (which immediately leads into the succession discussion where Antoninus speaks of "Asveirus my son") perfectly coherent. By recognizing both phrases in their proper context, the Talmud's nuanced preservation of Severus's complex identity is revealed, distinguishing him from prior Antonine emperors by acknowledging his true Severan origin while also acknowledging his son's role in the dynastic succession. This clarifies the identity and sets the stage for the following narrative concerning succession.

C. Imperial Succession and Tiberias's Elevation (Avodah Zarah 10b):

Building directly on the elucidation of "Asveirus bar Antoninus" as Caracalla, the Talmud immediately records Antoninus's two critical wishes from the Roman Senate: "I desire that Asveirus my son rule after me, and that Tiberias be made a kalanya (colony)." He laments that the Senate would grant only one. The crucial element here is Rabbi Judah's specific strategic advice to Antoninus, delivered through the riddle of the man on shoulders with a dove: "You ask them [the Senate] that 'Asveirus my son rule after me,' and tell Asveirus that he [the son] should make Tiberias a kalanya'." This detailed counsel for securing succession first and allowing the son to address Tiberias's status subsequently aligns remarkably with historical events during the Severan dynasty:

- Co-Regency Confirmed During Lifetime: Septimius Severus indeed dedicated significant effort to securing the succession of his sons. He elevated Caracalla to Augustus in 198 CE and Geta to Augustus in 209 CE, both while Severus himself was still alive. This direct fulfillment of Rabbi Judah's advice to ensure senatorial confirmation of a co-regent during the emperor's lifetime is a powerful historical parallel, demonstrating Severus's commitment to dynastic continuity. The riddle's structure, instructing the "lower" man (representing the current emperor) to command the "upper" man (the son) to act, perfectly encapsulates this strategy.

- Tiberias "Freed" by the Son: Following Severus's death, his son Caracalla (who, as Severus's son, was also an "Antoninus" by virtue of his paternal lineage and adopted name) issued the monumental Constitutio Antoniniana in 212 CE. This edict granted Roman citizenship to virtually all free inhabitants of the Empire. While the Talmud mentions a wish for "colony" status or tax relief, the granting of universal citizenship by Caracalla would have profoundly elevated the legal and fiscal status of Jewish cities like Tiberias, effectively "freeing" them from certain burdens and elevating their standing in a way that superseded the specific "colony" request. It represents a significant elevation of standing for its inhabitants, achieving the spirit, if not the letter, of Rabbi Judah's counsel, possibly at the urging of the Jewish leadership. This demonstrates a precise historical sequence where the first part of Rabbi Judah's advice (co-regency during the father's lifetime) was implemented by Severus, and the second part (Tiberias's elevation) was completed by his son, Caracalla, thereby fulfilling the complete counsel.

D. Strategic Counsel: The "Vegetable Plucking" Metaphor (Avodah Zarah 10b):

Immediately following the succession narrative, Antoninus complains to Rabbi Judah that "The Roman notables distress me." This problem was particularly acute with the Roman senatorial elite, from whom Severus faced multiple documented treasonous attempts throughout his reign. Rabbi Judah's advice, subtly given by uprooting "a radish from the row" in a garden before Antoninus, is interpreted by the Emperor as: "You kill them one by one, and do not contend with all of them [at once]."

Strategic Application by Severus: This counsel precisely mirrors the political strategy Septimius Severus demonstrably employed throughout his reign. After consolidating power through military victory, Severus systematically dismantled potential opposition within the Senate and Praetorian Guard, often through purges and executions. His elimination of figures like Clodius Albinus, and later the calculated downfall of Plautianus, exemplifies a patient, methodical approach to neutralizing threats rather than a sudden, comprehensive massacre that might provoke wider rebellion. This narrative, therefore, functions as a remarkably apt commentary on Severus's signature realpolitik. It underscores the intimate nature of the discussions between Emperor and Nasi, delving into the practicalities of imperial governance and survival.

E. The Necessity of Secrecy: "Bird of the Heavens" and the Tunnel:

The Talmud explicitly addresses the clandestine nature of the interactions between Antoninus and Rabbi Judah, reinforcing the high stakes involved. Following the "vegetable plucking" advice, the text poses: "And why not tell him explicitly?" Antoninus replies: "The Roman notables will hear of me and distress me." When pressed, "And why not tell him in a whisper?", the answer cites Ecclesiastes 10:20: "Because it is written: 'For a bird of the heavens will carry the voice.'" This highlights the extreme caution required for their consultations.

This concern was well-founded, as Severus faced numerous real and perceived treasonous plots, particularly from within the senatorial ranks. Compounding this pervasive atmosphere of suspicion and fear were the actions of the immensely powerful Praetorian Prefect, Gaius Fulvius Plautianus. Dio Cassius (76.15.1-2) records Plautianus's extraordinary influence, noting that he effectively overshadowed Severus himself, wielding power and accumulating wealth that eclipsed even the imperial family. His extensive network of spies and ruthless methods of suppression were well known, fostering a climate of profound paranoia across the Empire. Indeed, Plautianus's ambition was such that he virtually forced the marriage of his daughter, Plautilla, onto Caracalla in 202 CE, a union widely known to be detested by the young heir.

Such a volatile and high-stakes environment made clandestine consultations on sensitive matters of state survival an absolute necessity. This perfectly explains the emperor's extreme measures like the underground tunnel and the killing of slaves to ensure absolute secrecy, a theme vividly highlighted by the concluding anecdote of their relationship: "He [Antoninus] had a certain tunnel that led from his house to Rabbi's house. Every day he would bring two slaves, one he would kill at the entrance to Rabbi's house, and one he would kill at the entrance to his own house." This vivid detail underscores the profound political sensitivity of their consultations and the life-threatening risks associated with any breach of confidentiality, capturing the perilous reality of high-level political interactions in the Severan era and aligning perfectly with Severus's reign.

F. The "Gira" Story (Daughter's Illicit Relations, Avodah Zarah 10b):

In this highly cryptic narrative, Antoninus consults Rabbi Judah about his "daughter Gira" who engaged in "illicit relations" (איסורא). The subsequent discussion about punishment or mercy is conveyed through a precise, bidirectional sequence of coded plant messages, revealing a profound depth of understanding between the Emperor and the Patriarch. This exchange, interpreted through classic commentaries, offers a direct insight into the severe dilemma faced by Antoninus:

The text records the exchange as: "הֲוָה לֵיהּ הָהוּא בְּרַתָּא דִּשְׁמָהּ ״גִּירָא״, קָעָבְדָה אִיסּוּרָא. שַׁדַּר לֵיהּ ״גַּרְגִּירָא״, שַׁדַּר לֵיהּ ״כּוּסְבַּרְתָּא״, שַׁדַּר לֵיהּ ״כַּרָּתֵי״, שְׁלַח לֵיהּ ״חַסָּא״." (He [Antoninus] had a daughter whose name was 'Gira,' she was doing isura (illicit relations). He [Antoninus] sent him [Rabbi] 'gargira' (rocket/arugula); he [Rabpi] sent him [Rabbi] 'kusbarta' (coriander); he [Antoninus] sent him [Rabbi] 'karate' (leeks); he [Rabbi] sent him [Rabbi] 'chasa' (lettuce/mercy).)

Let's break down this symbolic dialogue with the aid of classic commentaries:

- "Gira" as Geta: We propose that "Gira" (גירא) is a deliberately veiled phonetic reference to Geta, Septimius Severus's younger son, who was indeed caught in a deadly rivalry with his brother Caracalla. The use of "daughter" serves as a code to obscure the identity of the powerful imperial male in such a sensitive matter.

- "Illicit Relations" as Political Subversion/Treason: The phrase "illicit relations" (isura), traditionally interpreted as sexual immorality, is here understood as a euphemism for Geta's perceived political 'treason' or dangerous allegiances, specifically with elements of the Roman Senate. Historical sources, notably Dio Cassius, record that Geta was seen as being 'overly friendly to the Senate,' an allegiance that his ambitious brother Caracalla later effectively weaponized to claim treason against Geta. This hidden political dimension points to Severus's deep concern about the loyalty of his sons and the stability of his dynastic succession, particularly given the ongoing senatorial opposition he himself faced.

- The Bidirectional Plant Messages and Their Interpretation (According to Classic Commentaries):

- Antoninus sends gargira (גרגירא - rocket/arugula): According to classic commentaries, Antoninus sending gargira signifies that Gira (Geta) has "let herself go astray" or "become corrupt." This plant choice by Antoninus indicates his recognition of the severity of the situation and Geta's deviation from acceptable conduct, expressing his distress or initial assessment of the problem.

- Rabbi Judah sends kusbarta (כּוּסְבַּרְתָּא - coriander): This remains the pivotal and most ambiguous response, reflecting Rabbi Judah's extreme caution in advising an emperor on such a life-and-death matter. Classic commentaries provide two primary interpretations for kusbarta:

- Rashi interprets kusbarta as a homonymic play on words meaning "slaughter the daughter" (כוס ברתא), suggesting a drastic, fatal solution.

- In contrast, R' Hananel suggests kusbarta implies "cover for the daughter", advocating discretion or concealment rather than public punishment or elimination.

This article posits that both interpretations are likely correct, and Rabbi Judah’s advice was, in fact, purposefully ambiguous. His choice of kusbarta strategically presents Antoninus with these two stark, yet veiled, options, allowing the Emperor to signal his true inclination without Rabbi Judah directly advocating for a specific, potentially dangerous, course of action.

- Antoninus sends karate (כַּרָּתֵי - leeks): In response to Rabbi Judah's ambiguous kusbarta, Antoninus sends karate. According to classic commentaries, karate (leeks) here signifies a direct question or challenge from Antoninus: "Do you want me to cut off my lineage?" This reveals the Emperor is grappling with the most extreme option – the elimination or permanent disinheritance of his son – and is seeking Rabbi Judah's clear endorsement or dissuasion for such a drastic, irreversible act following the ambiguity of the kusbarta message. This highlights the dire nature of the crisis and the profound trust Antoninus places in Rabbi Judah's counsel.

- Rabbi Judah sends chasa (חַסָּא - lettuce/mercy): This final message from Rabbi Judah serves as the unequivocal answer and plea. Its name is a direct phonetic play on the Aramaic word chasah (חסא), meaning "have mercy" or "pity." After Antoninus's direct, anguished question about severing his lineage, Rabbi Judah's final, unambiguous message is a clear appeal for clemency, compassion, or a less extreme solution than elimination.

The Purge and Geta's Perceived Threat: Historical accounts reveal that Severus himself faced numerous treasonous attempts from the senatorial elite throughout his reign. Later, Geta was indeed perceived by some, particularly by his ambitious brother Caracalla, as being 'overly friendly' to the Senate. This perceived allegiance could easily have been, and indeed later was, weaponized by Caracalla to claim treason against Geta. The question of whether Geta's perceived 'treason' (or potential future threat to the dynastic unity) needed to be 'slaughtered' or 'cut off from lineage' (implied by kusbarta and karate) versus being spared or handled with 'mercy' (implied by chasa) was a very real, high-stakes dilemma for Severus, grappling with the stability of his succession and the fierce rivalry between his sons. Rabbi Judah's ambivalence in the kusbarta response perfectly reflects the perilousness and uncertainty of this internal imperial struggle.

G. The Gold and Wheat Anecdote (Avodah Zarah 10b):

This anecdote, found later in the same Talmudic passage, describes Antoninus regularly sending Rabbi Judah lavish gifts of gold and wheat, indicating a continuous and generous relationship. When Rabbi Judah expresses no need, Antoninus states: "Let it be for those who come after you, so that they [the future emperors] will give to those who come after you, and those who come from among them [future emperors] should come out against them [future sages]." This seemingly cynical remark about future relations is consistent with Severus's pragmatic view of power and succession, emphasizing a transactional, though potentially beneficial, relationship between imperial authority and rabbinic leadership that was intended to endure beyond their lifetimes. It suggests Antoninus's understanding that future emperors would also need to cultivate the Jewish leadership, and might even be challenged by them, reinforcing the Nasi's long-term influence.

H. Why Common Alternative Identifications (e.g., Caracalla) Fall Short:

While various Roman emperors have been proposed as the Talmudic Antoninus—most commonly Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius, or Caracalla—each falls short of fully encompassing the breadth and specific details of the narratives when compared to Septimius Severus:

- Antoninus Pius (r. 138-161 CE): His reign was notably stable and peaceful, demonstrably lacking the pervasive internal strife and threats (as detailed in Section IV.E regarding Severus's court) that would necessitate the extreme clandestine meetings, violent purges ("vegetable plucking"), or desperate dynastic struggles (like the "Gira" story) depicted in the Talmud. Furthermore, Antoninus Pius rarely left Italy, making the sustained, intimate relationship with Rabbi Judah in Palestine geographically improbable.

- Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180 CE): While Marcus Aurelius possessed the philosophical depth that might align with some Talmudic dialogues, his reign was dominated by military campaigns on the Danube frontier, not in the East. Crucially, the sensitive political situations described—such as the explicit concern for securing senatorial approval for a son's succession, the systematic elimination of "notables," or the "Gira" story (referencing Geta and Plautianus)—are specific to the Severan era, not his.

- Caracalla (r. 211-217 CE as sole emperor; co-Augustus from 198 CE): Caracalla is often considered due to his Antonine name and presence in the East. However, several critical points contradict this identification as the primary Antoninus:

- Age and Nature of Relationship: While Caracalla was co-Augustus for years, the deep, philosophical, and long-standing mentorship implied by the Talmudic narratives with Rabbi Judah (who was by then an elderly, established leader) is far more fitting for a mature, founding emperor like Severus, whose extensive reign (193-211 CE) allowed for the development of such a bond with the Nasi, rather than a young, notoriously brutal, impulsive, and short-reigning Caracalla.

- Dynastic Concerns and Heirs: The most significant contradiction lies in the Talmudic Antoninus's explicit concern for ensuring the succession of 'Asveirus my son' and his general dynastic preoccupations. Caracalla himself had no biological or adopted sons at any point in his life. His reign was marked by the elimination of rivals, including his brother Geta, whom he famously murdered, not the establishment of a stable dynasty through an heir.

- The "Gira" Story Dynamic: While Caracalla ultimately murdered Geta, the Talmudic 'Gira' narrative (as meticulously analyzed in Section IV.F) describes a nuanced, multi-turn coded consultation between the emperor and Rabbi Judah concerning a severe dynastic problem involving a son's perceived 'illicit relations.' This intricate consultative process, involving veiled questions and ambiguous answers regarding the fate of a son or lineage, aligns far better with Severus's complex political maneuvering and his struggles with Geta's perceived senatorial allegiances—a dilemma that ultimately fueled their intense rivalry. Caracalla's actions, by contrast, were often characterized by impulsive brutality rather than the veiled, consultative political chess depicted in the Talmud.

By carefully considering the complete tapestry of the Talmudic narratives and cross-referencing them with the specific historical contexts and personalities of these emperors, Septimius Severus emerges as the only candidate who comprehensively aligns with all the nuanced details, from philosophical depth and Eastern presence to dynastic ambitions and specific political crises, including the critical period of Geta's early troubles.

V. Historical Context: The Severan Dynasty's Relevance to the Talmudic Encounters

Building upon the dynastic landscape introduced in Section II, this section illuminates the specific aspects of Septimius Severus's reign (193-211 CE) that uniquely align with the intimate and politically charged narratives of the Talmud. Severus, having ascended to the imperial throne in 193 CE and strategically adopted the Antonine name to legitimize his nascent dynasty (as discussed in Section II), dedicated immense effort to securing a stable succession for his sons, Caracalla and Geta. He elevated Caracalla to Augustus in 198 CE and Geta to Augustus in 209 CE, intending for them to rule jointly, yet their deep-seated rivalry ultimately erupted upon Severus's death in 211 CE, culminating in Caracalla's brutal murder of Geta.

Crucially for the Talmudic accounts, Severus's reign involved significant and prolonged imperial engagement in the Roman East. From 197 to 202 CE, Severus conducted extensive campaigns against the Parthian Empire and subsequently reorganized the Eastern provinces. During this period, the imperial court would have been established for extended durations in cities like Antioch, in close proximity to Judea and Galilee. This contrasts sharply with Antoninus Pius, who rarely left Italy, or Marcus Aurelius, whose foreign campaigns were primarily on the Danube frontier, offering scant opportunity for the sustained, intimate interactions depicted in the Talmud. It is this extensive Eastern presence, combined with the intense dynastic focus and internal volatilities of his court, that created the precise historical conditions for the nuanced and often clandestine dialogues between an emperor and Rabbi Judah as recorded in the Talmud.

A key element of this volatile internal dynamic was the immense power and pervasive influence of Severus's Praetorian Prefect, Gaius Fulvius Plautianus. His notorious ruthlessness and extensive network of spies contributed significantly to the atmosphere of paranoia at the imperial court. For a detailed examination of Plautianus's role and its direct bearing on the Talmudic narratives of secrecy, see Section IV.E.

Rabbi Judah the Prince, as the Patriarch (Nasi) of the Jewish community, held a unique position as both a revered religious leader and the officially recognized representative of his people to the Roman authorities. A figure of immense wealth and influence, his interactions with the imperial court would have been highly sensitive and likely conducted with utmost discretion, a necessary condition for the Talmud's portrayal of 'secret' encounters.

VI. Counter-Narrative and Historical Memory: The Talmud as a Corrective

The most significant contribution of this unified theory lies in its implications for understanding the nature of historical memory and the Talmud's role as a unique historical source. The prevailing Roman historical narratives of the Severan period, particularly those of Dio Cassius and later writers influenced by Macrinus's propaganda, are demonstrably biased. Dio, a senator, resented Severus's militarism and his elevation of non-senatorial figures, while he utterly loathed Caracalla for his brutality and the murder of Geta. Accounts sympathetic to Macrinus, who plotted Caracalla's assassination, would naturally seek to delegitimize his predecessor.

These biases have largely shaped the modern perception of Severus and Caracalla as ruthless, purely pragmatic rulers devoid of intellectual depth or nuance. By proposing Septimius Severus as the Talmudic Antoninus, this article suggests that the Talmud preserves a different, perhaps more intimate, view of the imperial court. It reveals a Severus who, despite his public image, was a complex statesman engaged in realpolitik but also open to philosophical inquiry and spiritual guidance from an authoritative, non-Roman sage. The documented secrecy of these interactions, exemplified by the deliberate distinction embedded in phrases like "Antoninus ben Asveirus," the strategic ambiguity of the kusbarta counsel, and the precise alignment of the "vegetable plucking" and succession narratives, thus becomes a testament to the sensitive nature of these interactions and a deliberate act of historical preservation, allowing for the transmission of sensitive information and alternative perspectives that could not be openly recorded in the Roman annals due to the direct and significant risk to Rabbi Judah and Severus themselves. The Talmud, therefore, should be recognized not as an ahistorical curiosity, but as a vital, albeit challenging, source that provides a corrective to the sometimes distorted and incomplete official histories.

VII. Conclusion

By identifying Septimius Severus as the singular "Antoninus" of the Talmudic narratives in Avodah Zarah 10a-10b (and related passages), this article offers a more cohesive, historically grounded, and intellectually satisfying interpretation of these enigmatic passages. The convergence of Severus's formal adoption of the Antonine name and associated titulature, his critical Eastern presence, his dynastic struggles, and the plausible interpretation of cryptic Talmudic details (such as "Antoninus bar Asveirus" as a clear dynastic identifier for Severus himself, the "Gira" story as a coded reference to Geta's perceived treasonous leanings towards the Senate and the fierce dynastic rivalry, with Rabbi Judah's strategically ambiguous counsel and Antoninus's direct challenge, the "vegetable plucking" metaphor reflecting Severus's realpolitik, and the precise alignment of the succession and Tiberias's elevation with historical Severan actions) collectively builds a robust case. This re-evaluation not only clarifies a long-standing historical puzzle in rabbinic literature but also profoundly enhances our understanding of the complex, often veiled, interactions between the Roman imperial center and the vibrant Jewish leadership in late antiquity, suggesting a deeper level of historical precision and counter-memory encoded within the Talmud than previously appreciated. This work invites further interdisciplinary engagement, allowing the rich tapestry of rabbinic narratives to illuminate previously obscured facets of Roman imperial history.

Comments

Post a Comment