Ancient Practices to Apophenia’s Modern Echoes

Intro:

The Torah, in Leviticus 19:26, 19:31, 20:6, and Deuteronomy 18:10-11, lists four prohibited practices—Ov, Yidoni, Me’onen, and Menachesh—grouped as methods of seeking hidden knowledge. The Talmud, Sanhedrin 65b-66a, provides definitions from Jewish sages, clarifying their ancient roles. Below, we detail each term, its English translation, and its context.

Auguries (Me’onen):

Me’onen is tied to divination, with the sages suggesting it includes observing cloud patterns or calculating auspicious times. Auguries, from Latin augurium (interpretation of signs), involve reading natural phenomena—often bird behavior or sky formations—for divine guidance. In the Roman Empire, augurs were state priests who watched birds’ flights or cries to sanction actions like battles or elections. The Ides of March, March 15, 44 BCE, became infamous when Julius Caesar ignored ominous bird signs and was assassinated, highlighting auguries’ cultural weight. A cumulus cloud might resemble a warrior's face, with the darker shadows forming the eyes and mouth, or a stratus cloud might take the form of a large snake.

Omens (Menachesh):

Menachesh means interpreting omens, per the Talmud—events like a bird’s flight, a deer crossing a path, or a dropped staff signaling fate. Omens are chance occurrences seen as portents of good or ill. In ancient Greece, a raven’s call might foretell disaster; Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” (the protagonist’s interactions with the raven reflect his descent from grief to psychosis) turns the bird’s “Nevermore” into a poetic omen of despair. Such signs shaped decisions across civilizations, from Mesopotamia to medieval Europe.

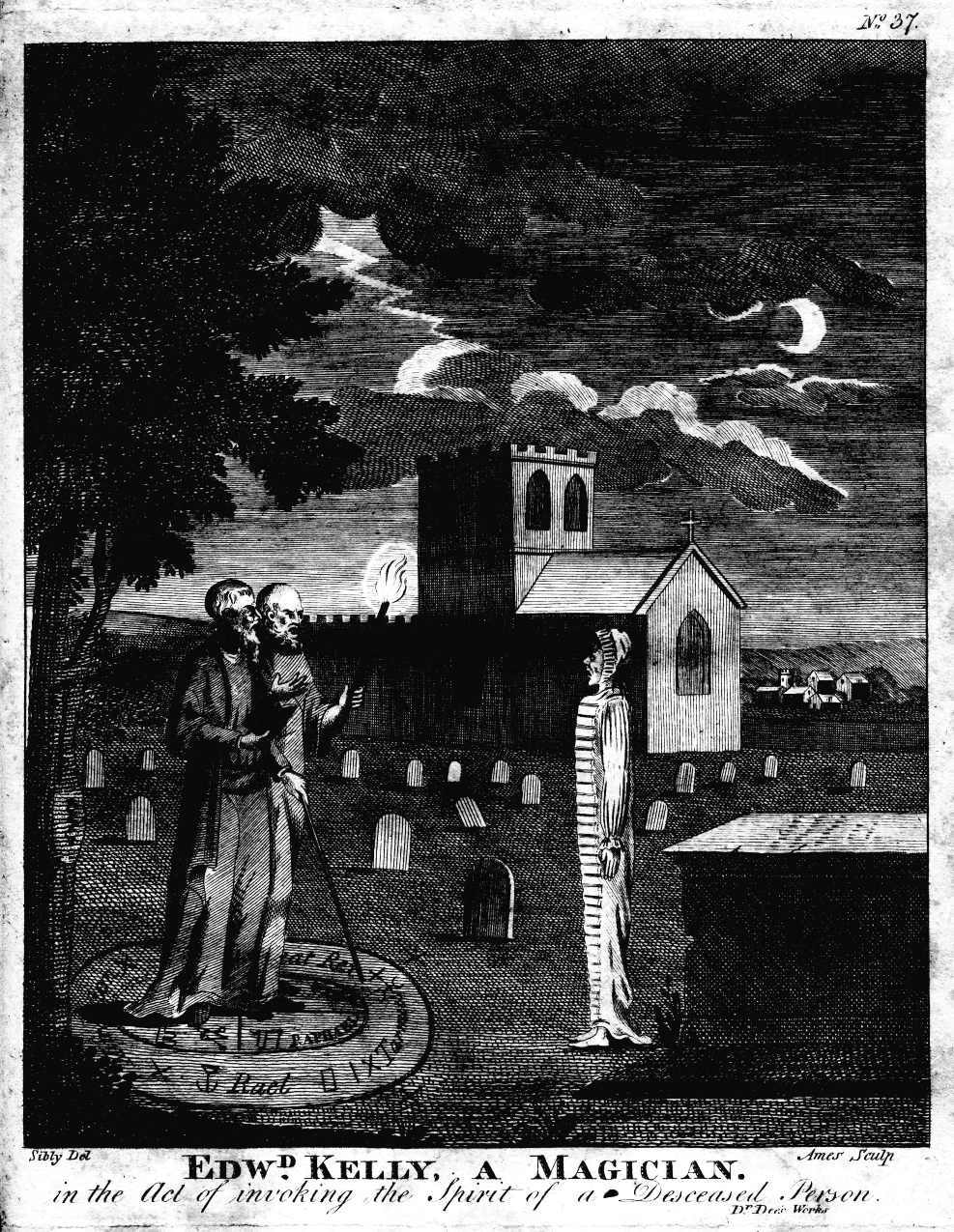

Necromancy (Ov):

Ov is defined as a medium who summons the dead, often through chants or rituals. Necromancy, from Greek nekros (dead) and manteia (divination), is consulting deceased spirits for insight. In ancient Egypt, priests invoked the dead to advise rulers; in Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus seeks Tiresias’ ghost. The practice assumes the departed hold wisdom, a notion the Torah forbids.

Spirit Consultation (Yidoni):

Yidoni involves knowing or contacting spirits, possibly by placing a bone in the mouth, say the sages. This spirit consultation uses a ritual object—here, a bone—as a conduit. Similar methods appear in shamanic traditions, where tools bridge human and spirit realms. The Yadua, linked to Yidoni, is described as human-like, tethered by an umbilical cord, its bone used in rites, pointing to a specific origin we’ll revisit.

The Common Thread and Clinical Lens:

These practices—auguries, omens, necromancy, spirit consultation—share a reliance on interpreting signs from nature, objects, or the unseen. To the ancients, this was a path to understanding; to the Torah, a prohibited detour. Modern psychology reframes this impulse as a cognitive tendency, one that, when unchecked, signals clinical pathology. What once guided a diviner’s gaze or a medium’s chant now appears in conditions like psychosis, where meaning is imposed on randomness. This bridge from ritual to diagnosis leads us to two key concepts.

Pareidolia:

Pareidolia, from Greek para (beside, instead of) and eidolon (image, form), describes the perception of familiar patterns—like faces or figures—in vague or unrelated stimuli. It’s closely tied to Me’onen, where a diviner might see shapes in the sky, perhaps a spear or a bird, and interpret them as a divine message. This tendency persists and remains common today, where people often imagine seeing various images in ordinary objects, like a face in a piece of toast. The augurs, however, believed these common occurrences held prophetic value, transforming everyday sights into omens of fate.

Apophenia:

Pareidolia belongs under an umbrella of related psychological phenomena called Apophenia. This concept, introduced by Klaus Conrad in 1958, refers to the tendency to find meaningful connections in random or unrelated data. Conrad connected it to early psychosis, such as schizophrenia, where individuals might see codes in numbers or hear voices in noise. In the DSM-5, apophenia aligns with the Psychoticism domain of the Alternative Model for Personality Disorders, which captures odd or eccentric behaviors and cognitions—like believing a random number sequence holds a hidden message—reflecting an overactive pattern-seeking mind (APA, 2013, p. 781). The paper “Apophenia as the Disposition to False Positives” (2019) notes that people high in psychoticism make more false-positive errors in tasks like digit identification, showing how apophenia can bridge normal perception and psychopathology. Let’s explore some of the more common forms of apophenia.

Pareidolia (Revisited):

Pareidolia influences perception in striking ways. In 1976, a NASA image from the Cydonia region of Mars showed what appeared to be a human face, dubbed the “Face on Mars,” though later photos revealed it as a natural ridge. In 2004, a grilled cheese sandwich with an image resembling the Virgin Mary sold for $28,000. In 2013, a stainless-steel kettle sold by JCPenney—the Michael Graves Design Bells and Whistles Tea Kettle—drew attention when social media users noted its resemblance to Adolf Hitler, leading to the removal of its billboards. These cases underscore pareidolia’s power: we see what we’re primed to find, even in the chaos of everyday objects.

Clustering Illusion:

Conspiracy Theories:

Yidoni and the Mandrake:

My prior work tied Yidoni’s Yadua—human-like, tethered by a cord, its bone used in rites—to the mandrake, Mandragora officinarum. Its root forks into a humanoid shape—legs, arms, torso—anchored by a taproot resembling an umbilical cord, its deliriant alkaloids like scopolamine and hyoscyamine inducing hallucinations, including voices. The ancients, perceiving this human-like form and experiencing psychoactive effects, interpreted the mandrake as a living conduit to the spirit world, its ‘cord’ suggesting a tie to the earth and beyond. We find a striking, almost identical parallel in Asia with Panax ginseng, whose roots similarly resemble the human form. For centuries, Asian cultures believed the ginseng plant grants ‘manly’ energy, aiding sexual performance and virility, a notion recorded in texts like the Shennong Bencao Jing (c. 200 CE). Even today, this association persists: ginseng teas and capsules, widely sold and consumed, promise stamina and libido. Both the mandrake and ginseng seem to have emerged via an apophenic leap, from murky resemblance to medicinal and spiritual power, though ginseng does contain some beneficial compounds for circulatory health. These twin tales, from Mediterranean shores to the Far East, reveal a shared human impulse: seeing a man in a root and weaving a story of life from it.

Humans as Pattern-Seeking Machines:

Humans are driven to find patterns, a trait that lets us categorize, predict, solve problems, and learn by linking cause and effect—skills essential for navigating a complex world. But this instinct, when unchecked, can lead us astray, as the mandrake and ginseng tales show, turning random occurrences into apophenic illusions. The Torah, in its wisdom, provides a grounding bulwark, a framework for navigating this spectrum by setting limits on practices like Yidoni and Me’onen.

Creativity and Apophenia:

Creativity, like apophenia, involves finding patterns, linking disparate elements in unexpected and interpretive ways. A poet might craft a metaphor from a fleeting shadow, seeing in it a symbol of loss, while an artist could paint a dreamlike scene where colors and shapes converge to evoke a hidden emotion, both thinking laterally to create something new. In surrealism, this takes a striking form: Salvador Dalí, in his 1931 work The Persistence of Memory, melts clocks over a barren landscape, blending time and space to evoke the fluidity of memory—an interpretive leap that mirrors apophenia’s pattern-seeking. The paper “Apophenia as the Disposition to False Positives” (2019) suggests this overlap stems from openness to experience, a trait tied to both creativity and apophenia, where creators often see “implausible patterns” that fuel their divergent thinking. Simon Kyaga’s studies (2011, 2013) found that artists have higher rates of bipolar disorder, and individuals with schizophrenia have a higher percentage of relatives in creative fields compared to others, further linking apophenia to creativity. Kyaga et al. (2011) note, “Mental illness may enhance divergent thinking” (British Journal of Psychiatry, 199:373). The Torah inspires creativity within bounds, encouraging expression that remains grounded in truth, unlike apophenia’s unchecked illusions. Yet what sets creativity apart?

Kyaga, S., et al. (2011). “Mental illness, suicide and creativity: 40-year prospective total population study.” British Journal of Psychiatry, 199, 373-379.

Functionality:

Creativity typically allows individuals to maintain normal functioning, engaging in daily life while producing art or ideas, whereas apophenia often disrupts this, especially in its extreme forms. An artist like Dalí could create The Persistence of Memory while still navigating relationships and responsibilities, but a psychotic person with apophenia might see every person on the train as a KGB spy trying to kill them, a belief that leads to paranoia and social withdrawal, severely impairing their ability to function. This difference in impact on daily life highlights what sets the two apart.

Internal Paradox:

Apophenia contains an internal paradox: it begins with openness and divergent thinking, allowing the mind to find patterns, but in its pathological form, this shifts to a rigid clinging to beliefs, even when challenged or proven detrimental. Someone with apophenia might initially see every train passenger as a KGB spy through an open, divergent lens, but then cling to this belief despite evidence to the contrary, showing a rigidity that contradicts the initial openness. In contrast, creativity, as seen in Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory, sustains its flexibility, blending time and space to evoke meaning while adapting to new ideas and contexts. This difference further separates the two.

Conclusion:

From Me’onen’s clouds to the mandrake’s roots, apophenia reveals a human impulse to find meaning, a trait that can fuel both creativity and delusion. The Torah offers a practical guide, limiting practices like Yidoni to ground our pattern-seeking in reality. This balance reminds us that while our minds seek connections, the challenge lies in avoiding the rigidity that can turn openness into delusion, ensuring our patterns support our ability to live and function in the world.

Comments

Post a Comment